Trump vs. Big Pharma Welfare Queens

-

Patrick Watson

Patrick Watson

- |

- January 17, 2017

- |

- Comments

No, he didn’t mean Russian hackers. He was talking about red-blooded American drug companies.

Trump went on: “Pharma has a lot of lobbyists and a lot of power, and there is very little bidding. We’re the largest buyer of drugs in the world, and yet we don’t bid properly, and we’re going to save billions of dollars.”

That last part isn’t quite correct, though.

Trump said there’s “very little bidding” when the government buys drugs. In fact, there’s no bidding at all when Medicare buys prescription drugs. The Bush-era legislation that created Medicare Part D bars the government from negotiating lower prices, despite it being the drug industry’s biggest customer by far.

That’s one reason pharmaceutical and biotechnology stocks performed so well in the last decade. And it’s why the prospect of losing that advantage pushed those sectors lower.

However, the Trump-inspired loss is actually minor compared to what another president once did to drug stocks. The dot-com bubble has some lessons we best not forget.

Photo: Getty Images

Party Like It’s 1999

Remember Y2K Eve? We all partied that December 31 because a) Prince had given us the perfect song for it, and b) we thought civilization might collapse when midnight struck.

Like what you're reading?

Get this free newsletter in your inbox regularly on Tuesdays! Read our privacy policy here.

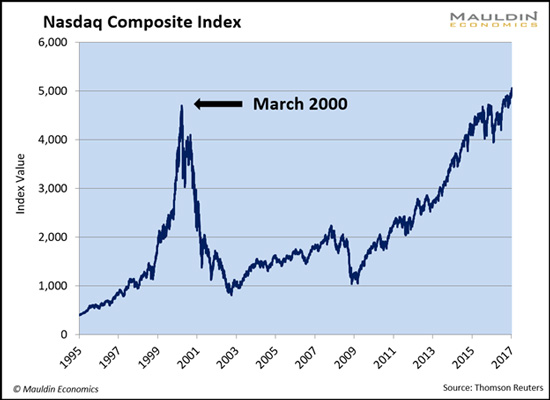

Fortunately, the electric grid stayed online, everyone survived, and the stock market continued its steady climb. The Nasdaq Composite Index had risen 86% in 1999, and folks expected more of the same in 2000.

They got it… for a few weeks.

At one point intraday on March 10, 2000, the Nasdaq showed a 26% year-to-date gain. Another double-your-money year seemed possible. Then this happened.

March 2000 turned out to be the Nasdaq’s all-time high and remained so for another 15 years.

That bear market had many causes, but Bill Clinton and the UK’s then-Prime Minister Tony Blair gave it the first push.

The Genome Crash

The Human Genome Project was a big deal in the 1980s and 1990s. Scientists were trying to “sequence” our DNA, i.e., map which genes go where. It was a laborious process, even with that period’s best technology, but it promised to create medical miracles.

There was actually kind of a race underway:

- Universities and research institutions all over the world cooperated in a government-backed initiative.

- Meanwhile, Celera, a private company led by biotech pioneer Craig Venter, was trying to do the same. Celera focused on genes it thought would lead to profitable drug breakthroughs.

Photo: Getty Images

Celera needed patent protection for its genome data in order to develop its business. No one was quite sure that was possible, but they invested like it was a sure thing.

Bad idea.

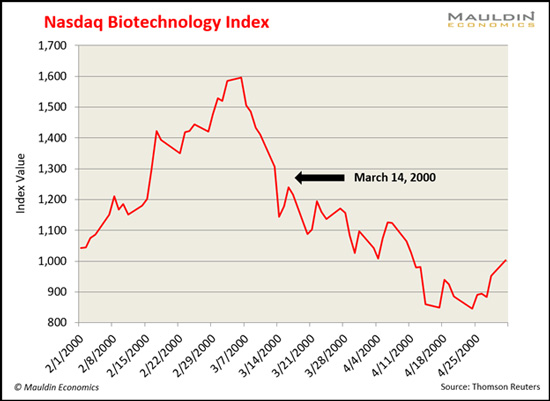

On March 14, 2000, President Clinton and British PM Blair popped the biotech bubble when they said genome data should be free to everyone.

Like what you're reading?

Get this free newsletter in your inbox regularly on Tuesdays! Read our privacy policy here.

You can see how much investors liked this idea in the Nasdaq Biotechnology Index. It had peaked a few days earlier but collapsed with the Clinton-Blair statement. In just a few weeks, sellers chopped the biotech index almost in half.

The March 15, 2000 New York Times recorded the carnage for posterity:

President Clinton and Prime Minister Tony Blair of Britain said yesterday that the sequence of the human genome should be made freely available to all researchers.

The statement led to a sharp sell-off in the stocks of biotechnology companies, which hope to profit by creating drugs based on genetic data.

The White House quickly said it did not intend to hurt the fledgling biotechnology industry, but investors who have made biotechnology stocks the darlings of the market were unconvinced. In frantic selling, they wiped away tens of billions of dollars in market value from the industry. Genomics companies, which are racing to produce a database of human DNA, were hit hardest, with some off more than 20 percent.

The drop was not confined to the biotechnology sector.

After briefly passing 5,000 in morning trading, the Nasdaq composite index, which is heavily weighted in technology stocks, fell steadily.

The index closed at 4,706.63, down 200.61 points, its second-largest point loss ever.

For investors, the drop is noteworthy, because biotechnology and Internet companies have led the stock market so far this year, while most other stocks have languished. Despite falling almost 13 percent yesterday, the Nasdaq biotech index remains up almost 30 percent this year, thanks to investors' belief that a new wave of drug discovery and gene therapy is imminent.

Biotech traders heard that “freely available” line and hit the sell button. That was smart, but even they didn’t know how bad it was going to get. The NYT writers didn’t realize they had just documented a generational stock market peak, either.

Did Trump just do the same thing again? We don’t know yet. As they say, history rarely repeats itself, but it often rhymes.

Political Favors Are Never Forever

Back in that 2000 crash, biotech industry leaders made a key mistake. They thought getting the government to protect their genetic data would be easy. Pay some lawyers, make some campaign contributions, and voilà, you have a legal monopoly. Ka-ching.

It turned out not to be so easy.

Photo: Getty Images

Today’s drug companies are making a similar mistake. Because they greased the right palms when Medicare drug coverage passed back in 2003, they think they have a permanent right to set their own prices – which taxpayers must pay.

In both cases, private companies assumed they were permanently entitled to certain government benefits.

Yes, I used that word: entitled.

The “entitlement mentality” you hear about isn’t just for food stamp recipients. It exists within large corporations too, and the amounts are often much greater.

Like what you're reading?

Get this free newsletter in your inbox regularly on Tuesdays! Read our privacy policy here.

But even if Washington grants you a benefit, today’s Congress can’t tie the hands of a future Congress.

Senators and Representatives can change their minds anytime they want—and they should change their minds, or at least consider it, when voters demand change through the electoral process.

That’s a risk factor investors forget at their peril.

If a business depends on some kind of government favor, don’t assume it will be there forever. Biotech investors found out in 2000 that political privileges are never a sure thing. The Trump era may teach Big Pharma shareholders the same hard lesson.

Will the rest of the market collapse, too, as it did in 2000? Ask me next year.

See you at the top,

Patrick Watson

@PatrickW

P.S. If you like my letters, you’ll love reading Over My Shoulder with serious economic analysis from my global network, at a surprisingly affordable price. Click here to learn more.

Patrick Watson

Patrick Watson