Politics Is Getting in the Way of China’s Critical Economic Reforms

- Customer Support

- |

- August 25, 2016

- |

- Comments

BY JACOB SHAPIRO

Two important reports were recently published on the current state of the Chinese economy. The first was the IMF’s annual review. It said the outlook for China’s near-term growth had improved. But, it pointed out that corporate debt is rising. Also, capital outflows for 2016 will equal 2015’s at $1 trillion.

The second report was China’s monthly release of investment data. This showed that fixed asset investment growth in China slowed to 8.1% in July. According to Caixin, that’s the slowest year-to-date fixed asset investment growth in 16 years.

These two reports outline the problems the Chinese economy faces. Ultimately, China’s problems are not only about facts and figures, but also about politics.

The IMF suggests ways to solve these problems. China must reduce corporate debt, restructure or even liquidate underperforming state-owned enterprises (SOEs), and accept lower growth. But, these economic policy decisions have political consequences. This makes it harder to achieve goals.

Economics outweighed by social and political costs

China knows it needs to reform SOEs. President Xi Jinping’s government has publicly said that it will cut 1.8 million jobs in the coal and steel sectors. However, the timeline has not been set.

The IMF wants China to cut 8 million jobs in a few key sectors. This is an unrealistic figure as the social and political costs outweigh the economic.

The corporate debt problem is similar. The IMF report sees rapid credit growth as the main issue. The highest credit levels are mostly in the northeastern and north-central provinces, where industry is the main driver of the economy.

Premier Li Keqiang spoke to provincial governors in July and told them to get rid of inefficiencies. In other words, they should not lend money to struggling SOEs.

Local officials take short-term view

Even though China is an authoritarian state, Beijing cannot simply dictate its will.

The advantages of a long-term approach are clear to the IMF… and even Beijing. But, real reform depends on local officials taking a long-term view.

This is hard when they are used to short-term solutions and a system that lets them profit from their activities. They also want to avoid protests, which may break out when SOEs fail and millions lose their jobs.

Beijing is caught between encouraging growth to maintain employment and accepting less growth. It must also boost domestic consumption.

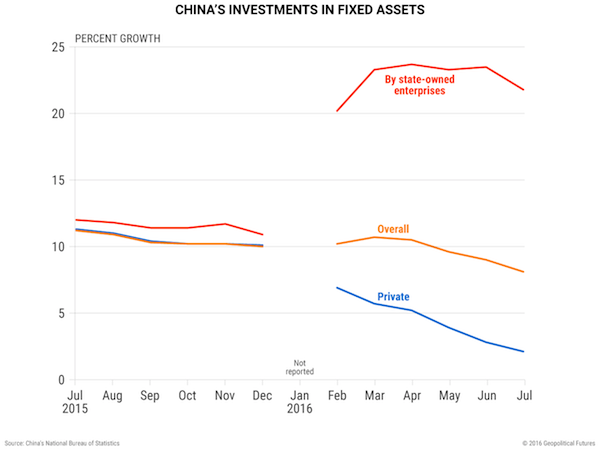

This is clear from the monthly investment numbers released by the Chinese. The report also shows that the trend began around December 2015.

The percentage growth between investment in fixed assets by SOEs and by private enterprises was roughly equal before December 2015.

Shocks in the stock markets in January, however, hurt investor confidence. In response, China relied on more stimuli in Q1 2016 than in any quarter since the 2008 financial crisis.

Private investment in fixed assets slowed to just 2.1% in July. This is despite China’s State Council issuing new guidelines in June to stimulate private investment.

In July, the government eased investment rules in free trade zones. It granted foreign investors permission to found companies in various sectors. Previously, companies would need to be co-owned by Chinese interests.

XI’s hands are tied

Meanwhile, SOE investment in fixed assets doubled between November and February. (China did not report any data for January.) Though growth slowed slightly in July, it remains at 21.8%. This is well above its previous levels, before China began pumping money into the system.

Chinese companies now increasingly depend on borrowing money to pay back loans. A Goldman Sachs report last month estimated that the debt service ratio for China was around 20%.

These companies are the same SOEs that China says it wants to restructure (and the IMF wants China to reform). But, China needs these SOEs to prop up economic growth and stimulate the domestic economy.

The IMF projects that Chinese GDP growth will fall slowly, from 6.6% in 2016 to 5.8% in 2021. This assumes that China will implement most of the proposed reforms.

The Chinese government wants to undertake many of these reforms, but it is constrained. This is why Xi is consolidating his power base. He knows that China must change and that Beijing must have the influence to do it. But, even a powerful Xi cannot eliminate corporate debt or conjure 8 million jobs out of thin air.

Join 250,000 readers of George Friedman’s Free Weekly Newsletter

George Friedman provides unbiased assessment of the global outlook—whether demographic, technological, cultural, geopolitical, or military—in his free publication This Week in Geopolitics. Subscribe now and get an in-depth view of the forces that will drive events and investors in the next year, decade, or even a century from now.