Blame IQ Tests for the Student Debt Problem

-

Patrick Watson

Patrick Watson

- |

- February 20, 2018

- |

- Comments

Everyone is worried about debt. Government debt, household debt, personal debt, corporate debt. We are in it up to our eyeballs and often beyond.

Debt is not always bad, though. The financial system can’t survive without it; banks and traders need debt to finance growth.

As usual, the key is moderation. Debt can be good if it helps a person grow their business... or invest in a good education. Well, at least that’s the theory.

Photo: Getty Images

Student debt should be productive—after all, it buys education that enhances your income. Yet for millions of Americans, that’s not what has happened, and the reason may surprise you.

Before we get into the details, let me quickly suggest you invest (debt-free) in another kind of education: a Virtual Pass to next month’s Strategic Investment Conference. For the first time ever, the Virtual Pass will include video recordings of every presentation and panel from the SIC 2018.

Even better, if you have some free time when the conference is happening, March 6-9, you can watch it live on your computer or mobile device.

The Virtual Pass includes some other nice benefits too. It’s the next best thing to being with us in San Diego, so check it out here.

Unpayable Debt

Like what you're reading?

Get this free newsletter in your inbox regularly on Tuesdays! Read our privacy policy here.

The New York Federal Reserve Bank publishes an always-interesting Quarterly Report on Household Debt and Credit. The Q4 2017 version came out last week.

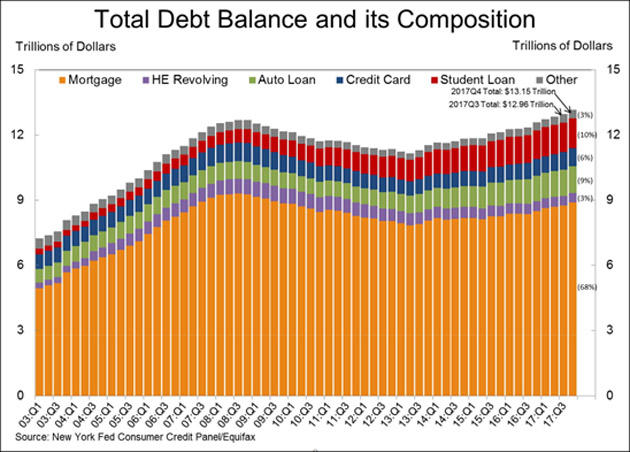

Collectively, Americans carried $13.15 trillion in debt as of year-end 2017.

As you can see, most of it is mortgage debt—about 71% of the total if you include home equity loans (“HE Revolving” in the chart).

Surprisingly, the next-largest category isn’t auto loans or credit cards. It’s student loans, which are now 10% of total debt. Their share has been growing steadily.

This might be okay if the debt enhanced the student’s financial security, but often that’s not the case. Millions of borrowers don’t achieve the desired results but remain stuck with the debt anyway.

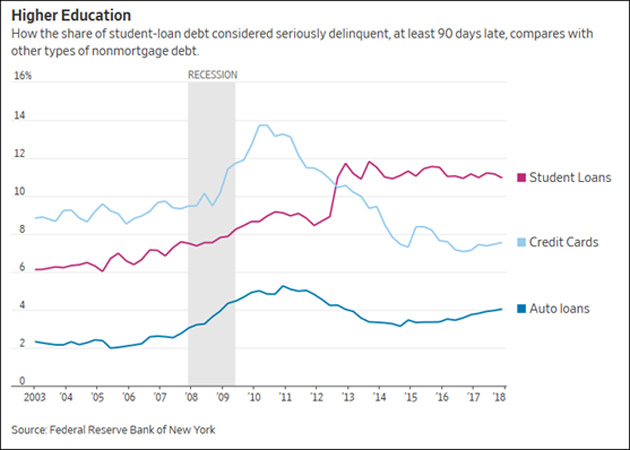

Wall Street Journal‘s higher-education reporter Josh Mitchell had an interesting story on this last week. Using the same New York Fed data, WSJ showed this info on loan delinquencies:

While delinquency rates for other forms of debt fell after the recession, student loans didn’t. As of year-end 2017, about 11% of nearly $1.4 trillion in student debt was at least 90 days delinquent.

It’s actually worse than that. Roughly half of student debt is held by borrowers who aren’t required to make payments yet because they are still in school, unemployed, or otherwise excused. Much of that debt would likely be delinquent too.

Also important: the delinquent loans tend to be small (less than $10,000) and held by borrowers who never earned degrees.

These borrowers probably thought they were doing the right thing. They wanted decent jobs and saw that having a college degree was necessary to get one.

Like what you're reading?

Get this free newsletter in your inbox regularly on Tuesdays! Read our privacy policy here.

So why is college the key to gainful employment? It hasn’t always been so.

It’s because employers require a degree as job qualification... and that’s partly the fault of IQ tests.

Photo: Getty Images

Unreasonable Tests

In 1971, the US Supreme Court decided a case called Griggs vs. Duke Power Co. The subject was employment requirements.

Duke’s practice—and many other companies at the time—was to give job applicants an IQ test. Supposedly, this let them hire qualified people, but some companies also used tests to discriminate by race. The 1964 Civil Rights Act banned pre-employment tests that were not “a reasonable measure of job performance.”

The court ruled that Duke’s tests were too broad and not directly related to the jobs performed, which made them illegal.

Furthermore, the court said employers had the burden of proving employment tests were necessary for business purposes and not racially discriminatory. That’s hard to prove, so many US companies stopped using pre-employment tests at all.

That left a problem, though. How were employers supposed to evaluate job applicants without illegally discriminating?

|

If you want to learn how to guide your portfolio through 2018 and beyond...

If you want first-hand insights and actionable ideas from these leading experts and 20 others, this is your opportunity! |

Soft Skills

Employers really want to know two different things about prospective workers:

- First, can this person perform the specific tasks that go with this job? That means operating a machine correctly, carrying boxes of a certain size and weight, writing computer code, etc. You might call these the “hard skills.”

- Second, there are soft skills. Is this person willing to stick with unpleasant assignments to the end? Will he show up on time? Can she work with others?

Those soft skills are harder to judge but critically important. They’re also what the Supreme Court made hard to test.

Like what you're reading?

Get this free newsletter in your inbox regularly on Tuesdays! Read our privacy policy here.

College sort of requires those same soft skills. A degree may not give you much useful knowledge, but it shows you have some basic intelligence and literacy. It also shows you will jump through hoops if your organization tells you to. Employers value those qualities.

The Griggs case said nothing about educational requirements. Employers remained free to require high school diplomas or college degrees… and the ruling gave them a big incentive to.

College degrees are convenient, legal substitutes for the kind of testing employers haven’t been able to use since the 1970s. So apart from whatever you learn in college, merely having the credential became necessary to career success.

As a result, everyone in the equation made certain choices.

- Employers: demand a college degree even for jobs that don’t require college-level skills.

- Workers: get a college degree even if you must take on debt.

- Colleges: Raise prices since so many students were begging for degrees.

This made college more expensive, forcing students to borrow more and more money. Politicians jumped in to promote and guarantee those loans. And here we are.

College Monopoly

In the Griggs case, the US Supreme Court effectively granted colleges a monopoly. They can discriminate based on testing—or really a long series of tests that lead to a degree. Employers can’t.

Like most monopolies, this one is inefficient. It creates unpayable debt that burdens students. Some of it eventually falls on taxpayers. Not ideal.

Methods exist to evaluate prospective workers without requiring college degrees, and without racial or other illegal discrimination. But there’s no incentive to try them when you can just screen out the non-college graduates and accomplish the same thing.

Resolving this impasse would help our debt problem and probably our employment problem as well. But the losers would be colleges and educational lenders, so don’t expect them to cooperate, unless someone forces them to.

See you at the top,

Like what you're reading?

Get this free newsletter in your inbox regularly on Tuesdays! Read our privacy policy here.

Patrick Watson

P.S. If you’re reading this because someone shared it with you, click here to get your own free Connecting the Dots subscription. You can also follow me on Twitter: @PatrickW.

P.S. If you like my letters, you’ll love reading Over My Shoulder with serious economic analysis from my global network, at a surprisingly affordable price. Click here to learn more.

Patrick Watson

Patrick Watson