Things That Make You Go Hmmm: That Was The Weak That Worked: Part II

- Patrick Cox

- |

- January 7, 2014

- |

- Comments

By Grant Williams | January 7, 2014

Last week, in Part I of "That Was The Weak That Worked," we reviewed the equity markets in an attempt to see how equity investors managed to scamper through 2013 with the friskiness of puppies when all about them lay doubt and potential disaster.

We found the answer in quantitative easing — of course.

This week we will take a look at how the bond market managed to navigate the same 12-month period and see what can be learned about 2013 in order to forecast for 2014.

Let's begin by considering the subject of logical fallacies — an endeavor rendered more obsolete with each passing day.

(Deus Diapente): The study of logical fallacies is useful in learning how to think instead of what to think. In learning how to deconstruct an argument, you learn how to efficiently construct your own thoughts, ideas, and arguments. You learn how to find fallacies in your own line of reasoning before they're even presented, which is a valuable methodology for learning how to think. Which is a lot more honest, liberating, and possibly more objective than simply regurgitating what society, teachers, parents, preachers, friends, or politicians tell us...

"Learning how to think instead of what to think"?

"Learning how to think instead of what to think"?

The very idea is enough to send many into an Austen-like swoon, and yet within this relatively simple construct lies a principle that, if it were applied to today's markets, would have every rational investor rushing headlong into the hills.

Allow me to demonstrate using everyone's favourite logical structure: the syllogism.

A syllogism is classified as a point-by-point outline of a deductive or inductive argument. Syllogisms normally contain two premises followed by a conclusion:

Premise 1:Miley Cyrus is the most talented musician of her generation. Premise 2:The most talented musician of every generation achieves legendary status. Conclusion:Miley Cyrus is a legend.

Simple.

The conclusion, from a purely logical standpoint, holds water. The problem comes when either of the first two premises is not accepted by the person to which they are proposed.

At that point, the argument starts to fall apart.

The common term for this kind of flawed argument is a "non sequitur," which literally means "it does not follow."

So let's apply the syllogistic approach to the concept of quantitative easing and see how we go:

Premise 1:Central banks have been printing money like lunatics. Premise 2:Their printing of money hasn't had any ill effects. Conclusion:Printing money doesn't have any ill effects.

Right then. There's our syllogism. Do you want to go first, or shall I?

Oh... ok.

Quantitative Easing IV (or "QE IV" — so-called because it was injected directly into the veins of the monetary system) was unveiled on December 11, 2012, when Ben Bernanke announced, as Operation Twist expired, that in addition to the ongoing QE3 program (which committed the Federal Reserve to buying $40 bn in MBS every month) he would sanction the additional buying of $45 bn in long-term Treasury securities. Every month. Forever. Until further notice.

The rest, as they say (whoever "they" are), is history.

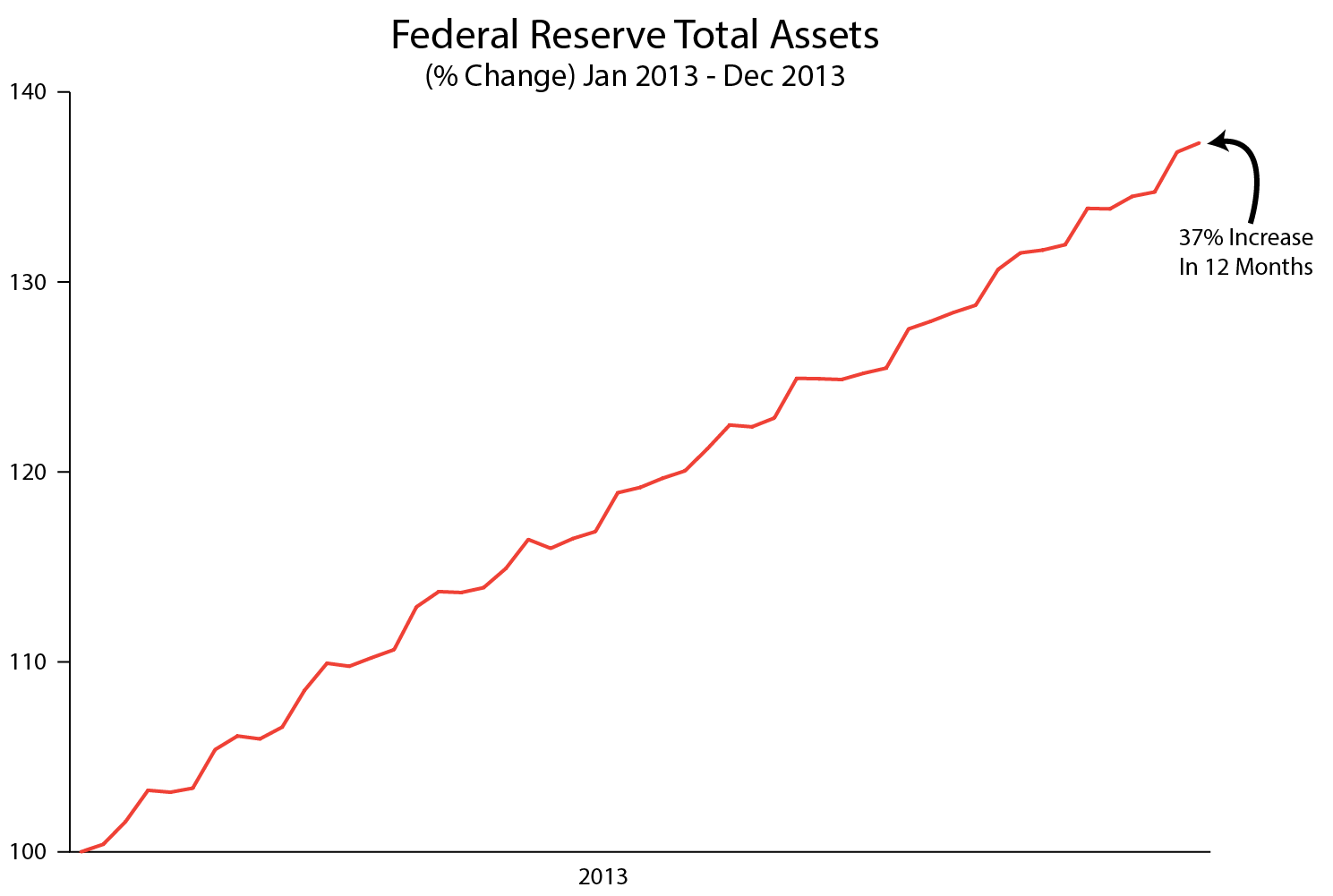

The effect on the Fed's balance sheet is plain to see:

Source: Bloomberg

That's a very steady, predictable line; and markets, as we have discussed, LOVE steady and predictable. The consistency of this curve underpinned the strength in equity markets this year, as I demonstrated last week. But in Bondville? Well, that's another story...

To continue reading this article from Things That Make You Go Hmmm… – a free weekly newsletter by Grant Williams, a highly respected financial expert and current portfolio and strategy advisor at Vulpes Investment Management in Singapore – please click here.