Thoughts from the Frontline: Transformation or Bust, Part 2

- Shannon Staton

- |

- August 12, 2014

- |

- Comments

In last week’s Thoughts from the Frontline (“Transformation or Bust”), my young colleague Worth Wray and I continued our groundbreaking series exploring the risks posed by China’s rapid private sector debt growth and its consumption-repressing, investment-heavy growth model that is quickly running out of steam. China is the true conundrum in the global economy. It is an outlier in the history of development, with no true analogues. And while there is much to be appreciative of and admired about China, there are clear danger signals.

As we have repeatedly explained in recent letters (“China’s Minsky Moment,” “Looking at the Middle Kingdom with Fresh Eyes,” & “Can Central Planners Save China’s Economic Miracle”), China’s overcapacity and over-indebtedness is not just the unfortunate consequence of hurried post-crisis stimulus, but an inherent, and one can even say necessary, by-product of the command and control approach that has underpinned China’s development since the days of Deng Xiaoping.

Worth and I have gone back and forth over this letter. He wrote the first draft; but as his thinking has continued to evolve during the editing process, Worth has struggled to see any happy path forward for China’s reformers, its 1.3+ billion citizens, or those economies and investors around the world who depend on the Middle Kingdom’s continued prosperity… at least not in the short term.

I sympathize with him, because as we worked through the issues I was reminded of my initial reactions when I began to explore the depths of the problems that constituted the subprime crisis. In that case there was not as much research to go through (the research on China is massive in content and scope), but mulling the evidence spurred the dawning awareness that subprime was going to be a problem unlike anything we had seen before, where everything seemed to be connected and you could clearly see that the situation would not end well; yet the extent of the problem was still not clear, at least early on. While my early estimates of losses were viewed as gloom and doom by almost every commentator, it turned out that I was overly optimistic.

Here, too, when you look at the depth and breadth of the problems and the difficulty of fixing them, it can be easy to get lost in the weeds. Envisioning a clear path through the issues from where we are today is not easy, though China certainly has more options than the world had with subprime by the middle of 2008, when there was so much toxic waste on the balance sheets of banks all over the world and there was no turning back. As we have emphasized in the past and will do today, China does have options. But each of the options has costs associated with it, and those costs are going up every day. Who pays and when is the simple question that most readers want to have answered, but therein lies the conundrum.

But rather than frame the issues further, let’s jump into this week’s letter (again noting that Worth is responsible for the bulk of the writing, with your humble analyst offering edits and suggestions here and there. Typically, the use of the pronoun “I” means Worth, and if I’ve chimed in with edits, you’ll see “us” or “we” instead. My goal was to keep this from turning into a three-part letter – though the topic deserves at least a book. )

Transformation or Bust, Part 2

After decades of marshaling resources, building out a modern infrastructure, and educating its workforce, China has amassed building blocks for economic development in abundant supply (in fact, they are in oversupply)… but the institutions and incentive structures underlying China’s socialist market economy are deeply and inherently skewed in favor of vested interests at all levels of government. If the People’s Republic has any hope of working through its growing debt burden, rebalancing to a more sustainable growth model, and becoming a truly developed economy in which innovation and entrepreneurship drive rising living standards over time, then old power structures and vested interests must give way to the rule of law and market-based incentives.

What happens next depends largely on the economic wisdom and political resolve of China’s reformers, who must find a way to gradually deleverage overextended regional governments and investment-intensive sectors while simultaneously rebalancing the national economy toward a more sustainable consumption-driven, service-intensive model. The trouble is, their efforts may be too little too late to slowly let the air out of a massive debt bubble, and even rapid productivity growth from “new-economy” sectors may not be enough to rebalance the debt equation.

History suggests that – even with a major wave of liberalizing reforms and a series of positive surprises – China’s economic “miracle” could end with a long period of painfully slow growth or with a banking crisis and sudden collapse. The extent to which the Chinese economy will go on being “manageable” (and we put that word in quotes because living through a Category 5 hurricane is manageable but not a great deal of fun and generally expensive) will depend a great deal on when the Chinese government decides to embrace the necessary reforms.

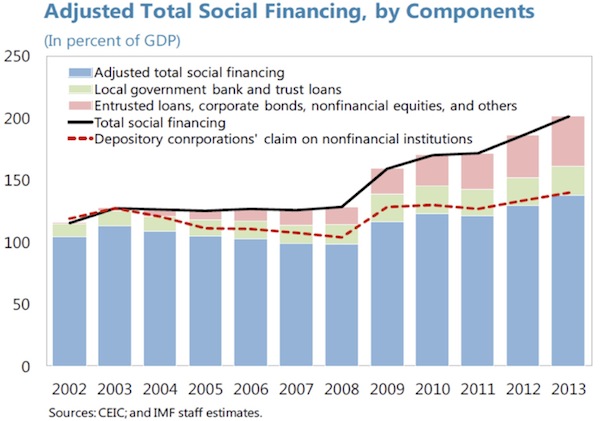

And now even the IMF is concerned about the escalating risks of a hard landing sometime between now and 2020 unless Beijing moves forward with its urgent reform agenda – reforms the IMF says should be specifically designed to prevent that hard landing. Echoing our own recently published thoughts, an IMF staff report published last week stated that China’s reliance on credit expansion and fixed-asset investment is becoming increasingly dangerous. Total social financing (the broadest official measure of domestic lending in the People’s Republic, as you can see in the graph below) has grown by 73% of GDP over the past five years, ranking China’s ongoing credit boom (which the IMF admits could be understated) among the top five most explosive instances of lending growth anywhere in the world since WWII.

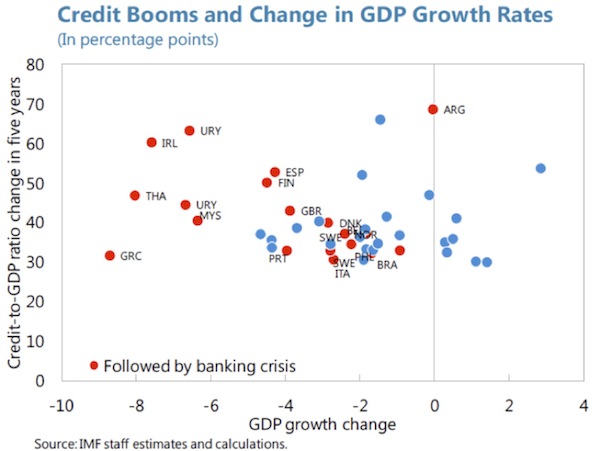

Looking at a sample of 43 major economies over the last fifty years, IMF economists Giovanni Dell’Ariccia, Deniz Igan, and Luc Laeven can find only four other cases of comparable lending growth… and each of those countries experienced a banking crisis and/or a sharp recession within three years of their respective booms.

In other words, there are no cases in modern history where an economy has managed to avoid an outright bust after experiencing rapid lending growth anywhere in the neighborhood of China’s ongoing credit boom. NONE. And even if we look to the 48 instances over the last 50 years where total social finance expanded by as little as 30% over five years (less than half the magnitude of China’s credit explosion), there is still a 50% chance of a banking crisis or an abrupt fall in growth during the post-boom period.

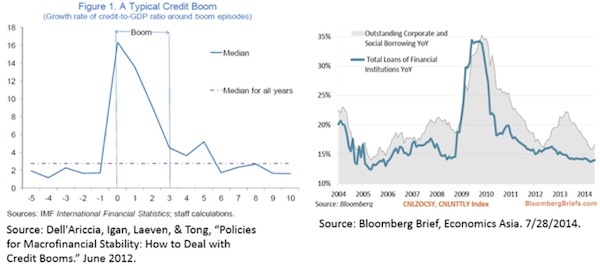

Moreover, the model for a “typical credit boom” (outlined in Dell’Ariccia, Igan, Laeven, & Tong’s 2012 paper “Policies for Macrofinancial Stability: How to Deal with Credit Booms”) suggests that painful post-boom adjustments tend to occur when the pace of credit growth simply cools back toward its long-term median (as opposed to outright deleveraging)… and that cooling process is already well advanced in the Middle Kingdom.

Notice, in the charts below, that China’s year-over-year growth rate in total social finance since 2004 basically looks like a more extreme version of the typical credit boom.

No one should EVER expect the IMF to come right out and say, “China is teetering on the edge of a crisis, and it has already wasted its opportunity to reform”; but the team of IMF staff economists was clearly not afraid to acknowledge how easily China’s risky “web of vulnerabilities” could tip into a full-blown financial crisis if measures to address them are implemented too abruptly. They highlight five sectors: real estate, corporations, local governments, banks, and in particular shadow banking. In almost every sector, the specter of significant to massive overleveraging is noted. It does not take a sophisticated analyst to be able to read between the lines of this report. For a bunch of sedate economists, this is the equivalent of standing on their desks and screaming.

To continue reading this article from Thoughts from the Frontline – a free weekly publication by John Mauldin, renowned financial expert, best-selling author, and Chairman of Mauldin Economics – please click here.