A Liquidity Crisis of Biblical Proportions Is Upon Us

- John Mauldin

- |

- May 17, 2018

- |

- Comments

BY JOHN MAULDIN

Last week, I mentioned an insightful comment my friend Peter Boockvar—CIO of Bleakley Advisory Group—made at dinner in New York: “We now have credit cycles instead of economic cycles.”

That one sentence provoked numerous phone calls and emails, all seeking elaboration. What did Peter mean by that statement?

In an old-style economic cycle, recessions triggered bear markets. Economic contraction slowed consumer spending, corporate earnings fell, and stock prices dropped. That’s not how it works when the credit cycle is in control.

Lower asset prices aren’t the result of a recession. They cause the recession. That’s because access to credit drives consumer spending and business investment.

Take it away and they decline. Recession follows.

The Illusion of Liquidity

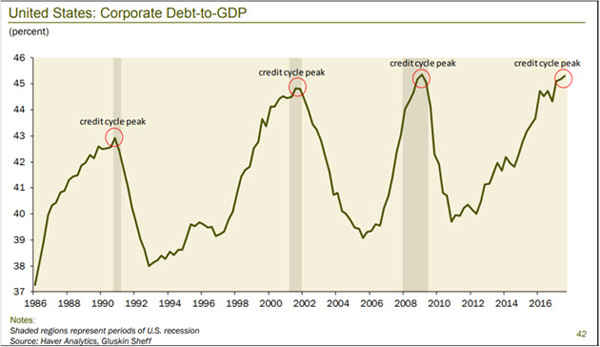

Corporate debt is now at a level that has not ended well in past cycles. Here’s a chart from Dave Rosenberg:

Source: Gluskin Sheff

The Debt/GDP ratio could go higher still, but I think not much more. Whenever it falls, lenders (including bond fund and ETF investors) will want to sell. Then comes the hard part: to whom?

You see, it’s not just borrowers who’ve become accustomed to easy credit. Many lenders assume they can exit at a moment’s notice. One reason for the Great Recession was so many borrowers had sold short-term commercial paper to buy long-term assets.

Things got worse when they couldn’t roll over the debt and some are now doing exactly the same thing again, except in much riskier high-yield debt. We have two related problems here.

- Corporate debt and especially high-yield debt issuance has exploded since 2009.

- Tighter regulations discouraged banks from making markets in corporate and HY debt.

Both are problems but the second is worse. Experts tell me that Dodd-Frank requirements have reduced major bank market-making abilities by around 90%. For now, bond market liquidity is fine because hedge funds and other non-bank lenders have filled the gap.

The problem is they are not true market makers. Nothing requires them to hold inventory or buy when you want to sell. That means all the bids can “magically” disappear just when you need them most.

These “shadow banks” are not in the business of protecting your assets. They are worried about their own profits and those of their clients.

Gavekal’s Louis Gave wrote a fascinating article on this last week titled, “The Illusion of Liquidity and Its Consequences.” He pulled the numbers on corporate bond ETFs and compared them to the inventory trading desks were holding—a rough measure of liquidity.

Louis found dealer inventory is not remotely enough to accommodate the selling he expects as higher rates bite more.

We now have a corporate bond market that has roughly doubled in size while the willingness and ability of bond dealers to provide liquidity into a stressed market has fallen by more than -80%. At the same time, this market has a brand-new class of investors, who are likely to expect daily liquidity if and when market behavior turns sour. At the very least, it is clear that this is a very different corporate bond market and history-based financial models will most likely be found wanting.

The “new class” of investors he mentions are corporate bond ETF and mutual fund shareholders. These funds have exploded in size (high yield alone is now around $2 trillion) and their design presumes a market with ample liquidity.

We barely have such a market right now, and we certainly won’t have one after rates jump another 50–100 basis points.

Worse, I don’t have enough exclamation points to describe the disaster when high-yield funds, often purchased by mom-and-pop investors in a reach for yield, all try to sell at once, and the funds sell anything they can at fire-sale prices to meet redemptions.

In a bear market you sell what you can, not what you want to. We will look at what happens to high-yield funds in bear markets in a later letter. The picture is not pretty.

Leverage, Leverage, Leverage

To make matters worse, many of these lenders are far more leveraged this time. They bought their corporate bonds with borrowed money, confident that low interest rates and defaults would keep risks manageable.

In fact, according to S&P Global Market Watch, 77% of corporate bonds that are leveraged are what’s known as “covenant-lite.” That means the borrower doesn’t have to repay by conventional means.

Somehow, lenders thought it was a good idea to buy those bonds. Maybe that made sense in good times. In bad times? It can precipitate a crisis. As the economy enters recession, many companies will lose their ability to service debt, especially now that the Fed is making it more expensive to roll over—as multiple trillions of dollars will need to do in the next few years.

Normally this would be the borrowers’ problem, but covenant-lite lenders took it on themselves.

The macroeconomic effects will spread even more widely. Companies that can’t service their debt have little choice but to shrink. They will do it via layoffs, reducing inventory and investment, or selling assets.

All those reduce growth and, if widespread enough, lead to recession.

Let’s look at this data and troubling chart from Bloomberg:

Companies will need to refinance an estimated $4 trillion of bonds over the next five years, about two-thirds of all their outstanding debt, according to Wells Fargo Securities. This has investors concerned because rising rates means it will cost more to pay for unprecedented amounts of borrowing, which could push balance sheets toward a tipping point. And on top of that, many see the economy slowing down at the same time the rollovers are peaking.

“If more of your cash flow is spent into servicing your debt and not trying to grow your company, that could, over time—if enough companies are doing that—lead to economic contraction,” said Zachary Chavis, a portfolio manager at Sage Advisory Services Ltd. in Austin, Texas. “A lot of people are worried that could happen in the next two years.”

The problem is that much of the $2 trillion in bond ETF and mutual funds isn’t owned by long-term investors who hold maturity. When the herd of investors calls up to redeem, there will be no bids for their “bad” bonds.

But they’re required to pay redemptions, so they’ll have to sell their “good” bonds. Remaining investors will be stuck with an increasingly poor-quality portfolio, which will drop even faster.

Wash, rinse, repeat. Those of us with a little gray hair have seen this before, but I think the coming one is potentially biblical in proportion.

Get one of the world’s most widely read investment newsletters… free

Sharp macroeconomic analysis, big market calls, and shrewd predictions are all in a week’s work for visionary thinker and acclaimed financial expert John Mauldin. Since 2001, investors have turned to his Thoughts from the Frontline to be informed about what’s really going on in the economy. Join hundreds of thousands of readers, and get it free in your inbox every week.