Capital Gains Problem

-

Patrick Watson

Patrick Watson

- |

- April 27, 2021

- |

- Comments

I saw a funny-but-true meme last week. It was about the food we grow.

We humans think farming is how we feed ourselves. But if you think longer term, the plants are actually farming us. They help us grow, then we die and go in the ground… to feed the plants.

Economics is the same way. Your time horizon matters.

Whenever we put this pandemic behind us, the economy will certainly be better… but it won’t be great. We had even bigger problems before the virus struck.

Bigger problems than mass unemployment and business failures? Yes. They were different problems, to be sure. They unfolded slowly and less noticeably, but they were quite real.

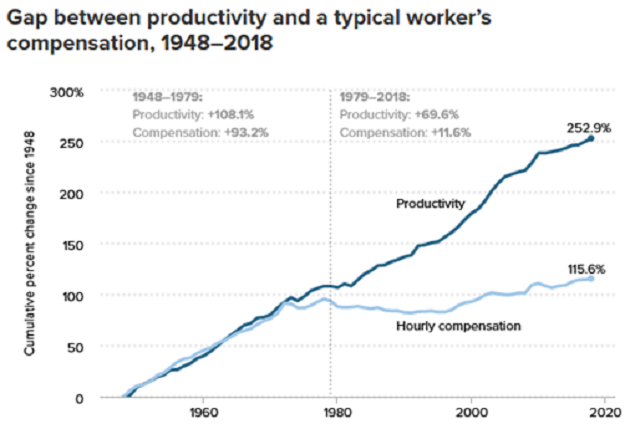

Here’s the core issue in one chart.

Source: Economic Policy Institute via Ed Harrison

The average worker’s productivity has been growing steadily since World War II. Until about 1979, average hourly wages grew at about the same rate. Then something changed: Productivity kept growing, wages didn’t.

Like what you're reading?

Get this free newsletter in your inbox regularly on Tuesdays! Read our privacy policy here.

What would cause this?

Take the top line first. Productivity gains are usually the result of investment: workers gain new skills, employers buy better tools or equipment, etc. These require capital.

So it may not be coincidence that tax changes in 1978 and 1981 gave preferential treatment to investment income, i.e., capital gains.

Subsidized by lower tax rates, employers invested in labor-saving technology and generated far greater output without increasing labor input. Hence, less need to raise wages. This led to a relative decline in middle class living standards and a variety of social ills.

Preferential Treatment

The tax preference for investment over labor is still in place today. I think most people don’t understand how big it is, either. Let’s walk through this.

Imagine two taxpayers, Tom and Jerry. For simplicity, we’ll assume both are unmarried and don’t have any state or local taxes.

- Tom has a job with a $100,000 salary—well above average, but not “wealthy.” After deductions, his 2020 taxable income was $85,000.

- Jerry has no job. He has a pile of inherited cash he uses to buy and sell stocks, which he always holds for at least a year. In 2020 he realized a net $85,000 in capital gains.

Both have the same taxable income. So how much do they pay?

According to the IRS tax tables, Tom’s income tax is $14,490. He also pays $7,650 in payroll taxes, for a total of $22,140. That’s 22.1% of his gross income. The income tax alone was 14.5% of his gross income.

Jerry’s only income is $85,000 in long-term capital gains. His tax rate is 0% on the first $40,000 and 15% on the remaining $45,000. He has no payroll tax. So his total taxes are $6,750, or 7.9% of his income.

This difference is magnified at higher income levels. People who get most of their income from capital gains pay no more than 20%. It would be 37% if they received the same income as salary.

Too Much Capital

Like what you're reading?

Get this free newsletter in your inbox regularly on Tuesdays! Read our privacy policy here.

With that kind of difference, it’s no surprise wealthy people try to receive most of their income as capital gains. Corporate CEOs who get relatively small salaries but giant stock option grants sometimes pay lower tax rates than workers earning much less.

Our tax code does this on purpose. Why?

It kind of made sense at first. Congress uses the tax code to encourage behavior it thinks useful, like homeownership. Savings and investment boost economic growth, so rewarding them should help everyone.

That was certainly so back around 1980. Sky-high interest rates meant capital was in short supply. Getting it into productive uses required some coaxing.

Today there is no shortage of investment capital. Crazily rising stock prices suggest we may have too much of it. Yet the tax code still rewards investment more than labor.

Economist Michael Pettis explained why this may be a problem in a short Twitter thread last weekend.

In an economy in which businesses want to invest in increasing productive capacity, but cannot do so because they are constrained by scarce savings and the high cost of capital, we need the savings of the rich to allow businesses to fund these investments, and the more that goes to the rich, perhaps the better…

It has been a little hard to argue—for many years, perhaps even many decades—that the problem faced by businesses in the US (or in Europe or Japan, for that matter) is their inability to access cheap savings.

In that case their unwillingness to expand investment more rapidly must be the consequence either of high levels of uncertainty, including policy uncertainty, which isn't what the stock markets seem to be suggesting, or a lack of sustainable demand to justify investment.

If it is the latter, then a tax system that directs income into more savings is worse for investment than one that directs income into more real demand, whether that demand comes from government infrastructure spending or higher consumption driven by greater household income at the bottom half of the income distribution.

In other words, we might be in better shape if government policy rewarded purchases of real goods and services, instead of investment. For example, imagine if wealthy people built bigger mansions instead of buying stocks. It would create demand for building materials, furniture, etc., and jobs producing them.

Note, equalizing the tax rates doesn’t have to mean raising them—though it could, and possibly will, if the latest White House tax proposal passes. (Details are still sketchy as I write this.)

The bigger structural question is whether it makes sense to give investment income preferential treatment over labor.

Ending that preference might be better for everyone, including investors, if it helps the economy grow more equitably and sustainably.

Like what you're reading?

Get this free newsletter in your inbox regularly on Tuesdays! Read our privacy policy here.

See you at the top,

Patrick Watson

@PatrickW

P.S. If you like my letters, you’ll love reading Over My Shoulder with serious economic analysis from my global network, at a surprisingly affordable price. Click here to learn more.

Patrick Watson

Patrick Watson