The Problem with Keynesianism

“The belief that wealth subsists not in ideas, attitudes, moral codes, and mental disciplines but in identifiable and static things that can be seized and redistributed is the materialist superstition. It stultified the works of Marx and other prophets of violence and envy. It frustrates every socialist revolutionary who imagines that by seizing the so-called means of production he can capture the crucial capital of an economy. It is the undoing of nearly every conglomerateur who believes he can safely enter new industries by buying rather than by learning them. It confounds every bureaucrat who imagines he can buy the fruits of research and development.

“The cost of capturing technology is mastery of the knowledge embodied in the underlying science. The means of entrepreneurs’ production are not land, labor, or capital but minds and hearts….

“Whatever the inequality of incomes, it is dwarfed by the inequality of contributions to human advancement. As the science fiction writer Robert Heinlein wrote, ‘Throughout history, poverty is the normal condition of man. Advances that permit this norm to be exceeded – here and there, now and then – are the work of an extremely small minority, frequently despised, often condemned, and almost always opposed by all right-thinking people. Whenever this tiny minority is kept from creating, or (as sometimes happens) is driven out of society, the people slip back into abject poverty. This is known as bad luck.’

“President Obama unconsciously confirmed Heinlein’s sardonic view of human nature in a campaign speech in Iowa: ‘We had reversed the recession, avoided depression, got the economy moving again, but over the last six months we’ve had a run of bad luck.’ All progress comes from the creative minority. Even government-financed research and development, outside the results-oriented military, is mostly wasted. Only the contributions of mind, will, and morality are enduring. The most important question for the future of America is how we treat our entrepreneurs. If our government continues to smear, harass, overtax, and oppressively regulate them, we will be dismayed by how swiftly the engines of American prosperity deteriorate. We will be amazed at how quickly American wealth flees to other countries....

“Those most acutely threatened by the abuse of American entrepreneurs are the poor. If the rich are stultified by socialism and crony capitalism, the lower economic classes will suffer the most as the horizons of opportunity close. High tax rates and oppressive regulations do not keep anyone from being rich. They prevent poor people from becoming rich. High tax rates do not redistribute incomes or wealth; they redistribute taxpayers – out of productive investment into overseas tax havens and out of offices and factories into beach resorts and municipal bonds. But if the 1 percent and the 0.1 percent are respected and allowed to risk their wealth – and new rebels are allowed to rise up and challenge them – America will continue to be the land where the last regularly become the first by serving others.”

– George Gilder, Knowledge and Power: The Information Theory of Capitalism

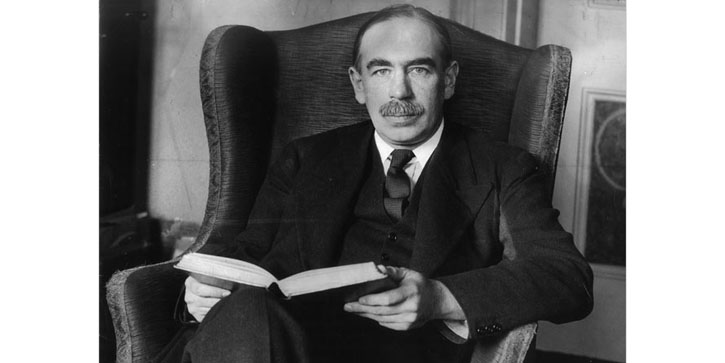

“The ideas of economists and political philosophers, both when they are right and when they are wrong are more powerful than is commonly understood. Indeed, the world is ruled by little else. Practical men, who believe themselves to be quite exempt from any intellectual influences, are usually slaves of some defunct economist.”

– John Maynard Keynes

“Nothing is more dangerous than a dogmatic worldview – nothing more constraining, more blinding to innovation, more destructive of openness to novelty.”

– Stephen Jay Gould

I think Lord Keynes himself would appreciate the irony that he has become the defunct economist under whose influence the academic and bureaucratic classes now toil, slaves to what has become as much a religious belief system as it is an economic theory. Men and women who display an appropriate amount of skepticism on all manner of other topics indiscriminately funnel a wide assortment of facts and data through the filter of Keynesianism without ever questioning its basic assumptions. And then some of them go on to prescribe government policies that have profound effects upon the citizens of their nations.

And when those policies create the conditions that engender the income inequality they so righteously oppose, they prescribe more of the same bad medicine. Like 18-century physicians applying leeches to their patients, they take comfort in the fact that all right-minded and economic scientists and philosophers concur with their recommended treatments.

This week, let’s look at the problems with Keynesianism and examine its impact on income inequality.

But first, let me note that Gary Shilling has agreed to come to our Strategic Investment Conference this May 13-16 in San Diego, joining a star-studded lineup of speakers who have already committed. This is really going to be the best conference ever, and you need to figure out how to make it. Early registration pricing goes away at the end of this week. My team at Mauldin Economics has produced a short, fun introductory clip featuring some of the speakers; so enjoy the video, check out the rest of our lineup, and then sign up to join us.

This is the first year we have not had to limit our conference to accredited investors; nor are we limiting attendance from outside the United States. We have a new venue that will allow us to adequately grow the conference over time. But we will not change the format of what many people call the best investment and economic conference in the US. Hope to see you there. And now on to our letter.

Ideas have consequences, and bad ideas have bad consequences. We started a series two weeks ago on income inequality, the current cause célèbre in economic and political circles. What spurred me to undertake this series was a recent paper from two economists (one from the St. Louis Federal Reserve) who are utterly remarkable in their ability to combine more bad economic ideas and research techniques into one paper than anyone else in recent memory.

Their even more remarkable conclusion is that income inequality was the cause of the Great Recession and subsequent lackluster growth. “Redistributive tax policy” is suggested approvingly. If direct redistribution is not politically possible, then other methods should be tried, the authors say. I’m sure that, given more time and data, the researchers could have used their methodology to ascribe the rise in teenage acne to income inequality as well.

So what is this notorious document? It’s “Inequality, the Great Recession, and Slow Recovery,” by Barry Z. Cynamon and Steven M. Fazzari. One could ask whether this is not just one more bad economic paper among many. If so, why should we waste our time on it?

(Let me state for the record that I am sure Messieurs Cynamon and Fazzari are wonderful husbands and fathers, their children love them, and their pets are happy when they come home. In addition, they are probably outstanding citizens who are active in all sorts of good things in their communities. Their friends and colleagues enjoy convivial gatherings with them. I’m sure that if I were to sit down to dinner with them [not likely to happen after this letter], we would have a lively debate and hugely enjoy ourselves. This is not a personal attack. I simply mean to eviscerate as best I can the rather malignant ideas that they are proffering.)

That income inequality stifles growth is not simply the idea of two economists in St. Louis. It is a widely held view that pervades almost the entire academic economics establishment. Nobel prize-winning economist Joseph Stiglitz has been pushing such an idea for some time (along with Paul Krugman, et al.); and a recent IMF paper suggests that slow growth is a direct result of income inequality, simply dismissing any so-called “right-wing” ideas that call into question the authors’ logic or methodology.

The challenge is that the subject of income inequality has now permeated the national dialogue not just in the United States but throughout the developed world. It will shape the coming political contests in the United States. How we describe income inequality and determine its proximate causes will define the boundaries of future economic and social policy. In discussing multiple problems with the Cynamon-Fazzari paper, we have the opportunity to think about how we should actually address income inequality. And hopefully we’ll steer away from simplistic answers that conveniently mesh with our political biases.

I should note that my readers have sent me an overwhelming amount of research on income inequality that I’ve been wading through for the past week. Some of it is quite discomforting, and a great deal is politically incorrect, at least some of which is almost certain to offend my gentle readers. Who knew that income inequality is not due to the greedy rich but to marriage patterns or the size of households or any number of interesting correlated factors? The research will all be thought-provoking, and we’ll will cover it in depth next week; but today let’s stay focused on the ideas of defunct economists.

Why Is Economic Theory Important?

Some readers may say, this is all well and good, but it’s just economic theory. How does that matter to our investment portfolios? The direct answer is that economic theory drives the policies of central banks and determines the price of money, and the price of money is fundamental to the prices of all our assets. What central banks do can be either helpful or harmful. Their actions can dampen volatility in the short term while intensifying pressures that distort prices, forming bubbles – which always end in significant reversals, often quite precipitously. (Note that it is not always high asset values that tumble. It is just as possible for central banks to repress the value of some assets to such low levels that they become a coiled spring.)

As we outlined at length in Code Red, central banks have a very limited set of policy tools with which to address crises. While the tools have all sorts of unlikely names, they are essentially limited to manipulating interest rates (the price of money) and flooding the market with liquidity. (Yes, I know that they can impose changes in a few secondary regulatory issues like margins, reserves, etc., but these are not their primary functions.)

The central banks of the US and England are beginning to wind down their extraordinary monetary policies. But whenever the next recession or crisis hits in the US, England, or Europe, their reaction to the problem – and subsequent monetary policy – are going to be based on Keynesian theory. The central bankers will give us more of the same, but it will be in an environment of already low rates and more than adequate liquidity. You need to understand how the theory they’re working from will express itself in the economy and affect your investment portfolio.

I should point out, however, that central banks are not the primary cause of distorted economic policy. They are reacting to the fiscal policies and political realities of their various countries. Japan’s government ran up the largest government debt-to-equity ratio in modern times; and now, as a result, the Japanese Central Bank is forced to monetize that debt.

Leverage and the distorted price of money have been at the root of almost every bubble in the postwar world. It is tempting to veer off into a soliloquy on the history of the problems leverage creates, but let’s forbear for now and deal with Keynesian thinking about income inequality.

The Problem with Keynesianism

Let’s start with a classic definition of Keynesianism from Wikipedia, so that we can all be comfortable that I’m not coloring the definition with my own bias (and, yes, I admit I have a bias). (Emphasis mine.)

Keynesian economics (or Keynesianism) is the view that in the short run, especially during recessions, economic output is strongly influenced by aggregate demand (total spending in the economy). In the Keynesian view, aggregate demand does not necessarily equal the productive capacity of the economy; instead, it is influenced by a host of factors and sometimes behaves erratically, affecting production, employment, and inflation.

The theories forming the basis of Keynesian economics were first presented by the British economist John Maynard Keynes in his book The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money, published in 1936, during the Great Depression. Keynes contrasted his approach to the aggregate supply-focused “classical” economics that preceded his book. The interpretations of Keynes that followed are contentious, and several schools of economic thought claim his legacy.

Keynesian economists often argue that private sector decisions sometimes lead to inefficient macroeconomic outcomes which require active policy responses by the public sector, in particular, monetary policy actions by the central bank and fiscal policy actions by the government, in order to stabilize output over the business cycle. Keynesian economics advocates a mixed economy – predominantly private sector, but with a role for government intervention during recessions.

(Before I launch into a critique of Keynesianism, let me point out that I find much to admire in the thinking of John Maynard Keynes. He was a great economist and taught us a great deal. Further, and this is important, my critique is simplistic. A proper examination of the problems with Keynesianism would require a lengthy paper or a book. We are just skimming along the surface and don’t have time for a deep dive.)

Central banks around the world and much of academia have been totally captured by Keynesian thinking. In the current avant-garde world of neo-Keynesianism, consumer demand –consumption – is everything. Federal Reserve monetary policy is clearly driven by the desire to stimulate demand through lower interest rates and easy money.

And Keynesian economists (of all stripes) want fiscal policy (essentially, the budgets of governments) to increase consumer demand. If the consumer can’t do it, the reasoning goes, then the government should step in and fill the breach. This of course requires deficit spending and the borrowing of money (including from your local central bank).

Essentially, when a central bank lowers interest rates, it is trying to make it easier for banks to lend money to businesses and for consumers to borrow money to spend. Economists like to see the government commit to fiscal stimulus at the same time, as well. They point to the numerous recessions that have ended after fiscal stimulus and lower rates were applied. They see the ending of recessions as proof that Keynesian doctrine works.

There are several problems with this line of thinking. First, using leverage (borrowed money) to stimulate spending today must by definition lower consumption in the future. Debt is future consumption denied or future consumption brought forward. Keynesian economists would argue that if you bring just enough future consumption into the present to stimulate positive growth, then that present “good” is worth the future drag on consumption, as long as there is still positive growth. Leverage just evens out the ups and downs. There is a certain logic to this, of course, which is why it is such a widespread belief.

Keynes argued, however, that money borrowed to alleviate recession should be repaid when growth resumes. My reading of Keynes does not suggest that he believed in the continual fiscal stimulus encouraged by his disciples and by the cohort that are called neo-Keynesians.

Secondly, as has been well documented by Ken Rogoff and Carmen Reinhart, there comes a point at which too much leverage on both private and government debt becomes destructive. There is no exact number or way of knowing when that point will be reached. It arrives when lenders, typically in the private sector, decide that the borrowers (whether private or government) might have some difficulty in paying back the debt and therefore begin to ask for more interest to compensate them for their risks. An overleveraged economy can’t afford the increase in interest rates, and economic contraction ensues. Sometimes the contraction is severe, and sometimes it can be absorbed. When it is accompanied by the popping of an economic bubble, it is particularly disastrous and can take a decade or longer to work itself out, as the developed world is finding out now.

Every major “economic miracle” since the end of World War II has been a result of leverage. Often this leverage has been accompanied by stimulative fiscal and monetary policies. Every single “miracle” has ended in tears, with the exception of the current recent runaway expansion in China, which is now being called into question. (And this is why so many eyes in the investment world are laser-focused on China. Forget about a hard landing or a recession, a simple slowdown in China has profound effects on the rest of the world.)

I would argue (along, I think, with the “Austrian” economist Hayek and other economic schools) that recessions are not brought on by insufficient consumption but rather by insufficient income. Fiscal and monetary policy should aim to grow incomes over the entire range of the economy, and that is accomplished by increasing production and making it easier for entrepreneurs and businesspeople to provide goods and services. When businesses increase production, they hire more workers and incomes go up.

Without income there are no tax revenues to redistribute. Without income and production, nothing of any economic significance happens. Keynes was correct when he observed that recessions are periods of reduced consumption, but that is a result and not a cause.

Entrepreneurs must be willing to create a product or offer a service in the hope that there will be sufficient demand for their work. There are no guarantees, and they risk economic peril with their ventures, whether we’re talking about the local bakery or hairdressing shop or Elon Musk trying to compete with the world’s largest automakers. If they are hampered in their efforts by government or central bank policies, then the economy stagnates.

Keynesianism is favored by politicians and academics because it offers a theory by which government actions can become the decisive factor in the economy. It offers a framework whereby governments and central banks can meddle in the economy and feel justified. It allows 12 people sitting in a board room in Washington DC to feel that they are in charge of setting the price of money (interest rates) in a free marketplace and that they know more than the entrepreneurs and businesspeople do who are actually in the market risking their own capital every day.

This is essentially the Platonic philosopher king conceit: the hubristic notion that there is a small group of wise elites that is capable of directing the economic actions of a country, no matter how educated or successful the populace has been on its own. And never mind that the world has multiple clear examples of how central controls eventually slow growth and make things worse over time. It is only when free people are allowed to set their own prices as both buyers and sellers of goods and services and, yes, even interest rates and the price of money, that valid market-clearing prices can be determined. Trying to control those prices results in one group being favored over another.

In today's world, the favored group is almost always bankers and the wealthy class. Savers and entrepreneurs are left to eat the crumbs that fall from the plates of the well-connected crony capitalists and to live off the income from repressed interest rates. The irony of using “cheap money” to try to drive consumer demand is that retirees and savers get less money to spend, and that clearly drives down their consumption. Why is the consumption produced by ballooning debt better than the consumption produced by hard work and savings? This is trickle-down monetary policy, which ironically favors the very large banks and institutions. If you ask Keynesian central bankers if they want to be seen as helping the rich and connected, they will stand back and forcefully tell you “NO!” But that is what happens when you start down the road of financial repression. Someone benefits. So far it has not been Main Street.

And, as we will see as we examine the problems of the economic paper that launched this essay, Keynesianism has given rise to a philosophical framework that justifies the seizure of money from one group of people to give to another group of people. This is a particularly pernicious doctrine, as George Gilder noted in our opening quote:

Those most acutely threatened by the abuse of American entrepreneurs are the poor. If the rich are stultified by socialism and crony capitalism, the lower economic classes will suffer the most as the horizons of opportunity close. High tax rates and oppressive regulations do not keep anyone from being rich. They prevent poor people from becoming rich. High tax rates do not redistribute incomes or wealth; they redistribute taxpayers – out of productive investment into overseas tax havens and out of offices and factories into beach resorts and municipal bonds.

Surprise: You Can’t Spend More Than You Make

First off, let me acknowledge that not everything in the Cynamon-Fazzari paper is wrong. As they analyze the data, they make a number of correct observations. They use a great deal of sophisticated math (seriously) to prove the rather unsurprising conclusion that you can’t spend more than you make. While everyone else in the world had already pretty much assumed that was the case, economists themselves can now rest easy in the knowledge that it’s a mathematical certainty.

The authors demonstrate that there is a disparity in the growth of incomes between the top 5% and the “bottom” 95%. There is not as big a difference as their data suggests, since they don’t take into account the growing percentage of employment benefits and ignore government support programs; but that’s another story, maybe for next week. Nor do they acknowledge that the percentage of people making over $100,000 (in constant dollars) has essentially doubled in the last 30 years. So yes, there are more people who are better off than before. Far more people have somehow slipped into a very comfortable lifestyle despite the fact that those who are even wealthier are making even higher incomes.

But let’s look at some of the authors’ actual wording and conclusions. First off, this gem:

A thread of macroeconomic thinking, going back at least to Michal Kalecki, identifies a basic challenge arising from growing inequality. This approach begins with the assumption that high-income households (usually associated with profit recipients) spend a lower share of their income than others (typically wage earners). In this case, rising inequality creates a drag on demand that can lead to unemployment and even secular stagnation if demand is not generated from other sources.

Read that paragraph again. And then a third time. I acknowledge that this is a well-established strain of economic thinking, but so is Marxism. Both are wrong. The authors of this paper basically start with the proposition that because those dastardly entrepreneurs and businesspeople (whom they call “profit recipients,” as if profit were a dirty word) actually dare to save some of their money rather than spend it, they are harming the economy. How heartless and thoughtless of them. Don’t they know the economy needs their spending?

It is very difficult for me to believe that this passes as acceptable economic thought in any but socialist circles. For those of you who were forced to endure Economics 101, you may remember that Savings = Investment. In any real-world economic system, you have to have savings in order to have investment in order for the economy to grow. Further, it is blatantly flawed logic to assume that savings don’t become investments, through banks or other intermediaries. Generally, savings are actually leveraged to produce more investments (and thus eventual production and consumption) than if the “profit recipients” had simply spent the money themselves.

At the heart of the Keynesian conceit we see the conclusion that consumption is better than savings. Yes, I know, I’ve written many a time about Keynes’s Paradox of Thrift: “It is a good thing for individuals to save, but if everybody saves then there is less consumption.” That seems true on the surface and makes for one of those great sound bites that Keynesians are so good at delivering, but it has an inherent flaw. It assumes that savings don’t become investments that increase productivity, which in turn leads to the production of more goods and services, which ultimately creates income, which then creates more demand.

Without savings, nothing happens. Nothing. There has to be capital of some kind from somewhere in order for economic activity to happen. In the last three years productivity has simply fallen off the charts, down by almost 60% from the average of the previous 60 years. This is a continuation of a trend that began with a decrease in savings. Productivity growth is ultimately a product of savings, and it is productivity growth that will generate an increase in income for the country as a whole. While the topic deserves an entire letter of its own, it may be enough to state here that there are consequences to the fact that savings are close to an all-time low.

A static economy does not produce an increase in either overall income or wealth. It is only an economy that is growing as a result of a healthy level of savings and investment that can produce the results that Keynesian economists want: increased incomes for everyone. (And yes, I acknowledge, as I have in previous letters, that income distribution has been increasingly uneven in recent decades; but I contend that this is the fault of government policy, not the market.)

Your typical Keynesian economist is not willing to wait a reasonable period of time for savings to become investment. Such people, and the politicians they serve, want results today. And the only way to get results today is to get people to spend today, while the process of saving and investing takes time. Neo-Keynesian economists are ultimately teenage children who want the pleasure of spending and consuming today rather than thinking about the future. And I won’t even go into the burden we are placing on future generations by borrowing money to goose our current economy and expecting them to pay that money back so that we can have our party today. We are building toward a future intergenerational war that is going to be very intense once our children learn how we have misspent their future. But that’s yet another letter. Back to our current topic.

Cynamon and Fazzari note that a rising debt-to-income ratio is accompanied by rising asset prices (home values, for instance). According to them,

This evidence shows that the financial choices of the bottom 95 percent in response to the rise in inequality that began in the early 1980s were unsustainable. Balance sheets cannot deteriorate indefinitely; the “Minsky Moment” that marked the end of rising balance sheet fragility occurred on the eve of the Great Recession. Lending was cut off to the bottom 95 percent, home price growth stalled and then declined. The crisis had begun.… This result provides empirical support for the widely held view that, other things equal, rising inequality will create a drag on consumption spending.

Really? On page 6 they state that “U.S. aggregate demand growth was not excessive before the recession,” yet they clearly understand that the spending of the “bottom” 95% was fueled by increasing debt borrowed against rising home values. Still, they decry the fact that “Lending was cut off to the bottom 95 percent, home price growth stalled and then declined.”

Actually, I think the sequence was: home price growth began to falter; it became evident that the mortgage industry was rife with corruption and fraud (from top to bottom with the complicity of the regulators and, even worse, the rating agencies); and then lending was cut off. If memory serves correctly, it was cut off to damn near everyone. There was a reason that significant assets were selling for dimes on the dollar.

Rising inequality did not create a drag on consumer spending. Too much debt and leverage created a bubble in spending that was unsustainable. It was easy-money policies, low interest rates, and regulatory failure that created the problem. The “drag on consumer spending” was the result of too much borrowing and a bubble and not the result of an inability to borrow.

How can one state with a straight face that aggregate demand growth was not excessive before the recession? In what alternative universe were the authors living? It was clearly a bubble and unsustainable. There were numerous authorities – with the exception of economists and the Federal Reserve, of course – who said so. Even someone as generally clueless as your humble analyst (at least that’s my kids’ opinion) said so least a few dozen times in the years preceding the crisis.

This letter is getting to be as long as most of you can deal with, yet there is at least as much to cover in the rest of the Cynamon-Fazzari paper as we’ve dealt with so far; so I think it is reasonable for me to declare that “It’s time to hit the send button.” Next week we’ll examine the authors’ belief that the Great Recession was the result of income inequality and tackle several other equally pernicious ideas.

Argentina, South Africa, Europe, and Rand Paul

I am back home for another 10 ten days, and then a rather aggressive travel agenda confronts me. I will go on a part business trip, part working vacation to Cafayate, Argentina, with my partners at Mauldin Economics and lots of friends. Right now the plan is to go up to Bill Bonner’s hacienda (on a mere 500,000 acres) at 10,000 feet in the Andes, and at that point I may truly be disconnected for a few days. He says he has an internet link, but last year it somehow didn’t work for anybody but him. I think that is when I realized I have an addiction problem. I’m sure there’s a 12-step program out there on the web somewhere.

Then I fly back to Dallas, hang out for eight hours, and journey on to South Africa. Don’t ask. But it makes sense, in a very odd way, to spend three consecutive nights in an airplane. The things your humble analyst has to endure to go to the ends of the earth for research purposes. The fact that I might show up at the Royal Malewene for a few days of what will then be a much-needed vacation is just a pleasant side note to the journey. After that respite I’ll began a rather serious tour of South Africa on behalf of Glacier by Sanlam, a very-full-service financial firm. I am looking forward to that trip.

Then a trip is shaping up to Amsterdam, Brussels, and Geneva prior to my own Strategic Investment Conference in San Diego. And speaking of that conference, my good friend Kyle Bass of Hayman Capital Advisors will be one of our speakers, as he was last year; but in the runup to the conference Kyle and I are going to engage in an online conversation.

Many readers will recognize Kyle from the media acclaim he garnered when his investment successes were featured in Michael Lewis’s The Big Short. In addition to being one of the most articulate and engaging speakers I know, Kyle is just an all-around nice guy. I truly treasure the times I get to spend with him. They are all too few. Seriously, if you get a chance to listen to him, you should.

If you are a qualified purchaser or a licensed investment adviser qualified to make private placement recommendations, please join me and my partners at Altegris for an exclusive webinar featuring Kyle on Monday, March 31, at 1:00 p.m. EDT / 10:00 a.m. PDT. Be sure to register here (http://www.altegris.com/mauldinreg) for this event, as it will be one of the more interesting discussions I engage in this year.

Upon qualification by my partners at Altegris, you will receive an email invitation. I apologize for limiting this discussion to qualified purchasers and investment advisors, but we must follow the rules and regulations. I look forward to having you at this exclusive event. (In this regard, I am president and a registered representative of Millennium Wave Securities, LLC, member FINRA.)

Next week I will offer you an exclusive link to an interview of Janet Yellen that was done a few years ago by my friend Jim Bruce in the process of producing his boffo documentary Money for Nothing. It is rather extraordinary, and I am proud to be able to make it available to my readers.

In the meantime, let me offer you a rather optimistic view of the future. A few months ago there was an enthusiastic group of young men, still in high school, who wanted to interview me about Federal Reserve policy. I kid you not. They put the interview on video, and it became part of a short documentary about the effects of Federal Reserve policies on the younger generation. They submitted the documentary to a contest sponsored by C-SPAN. There were 2,355 total submissions, and their video placed second. The outcome had nothing to do with the adeptness of your humble analyst in handling off-the-cuff remarks, but rather to these kids’ extraordinary talents, which resulted in a high-quality video and a surprisingly in-depth understanding of the topic. You can see the video here. Colleges around the country should be begging for youth like these young men to attend their schools.

Finally, I had a rather extraordinary opportunity to attend a small private dinner with Senator Rand Paul this last Tuesday. Also in attendance were old friends George Gilder and Rob Arnott, new friends Stephen Moore and David Malpass, plus a few others. It is not often I get to be the radical liberal at the table, but there I was. We were there to discuss monetary policy, but the conversation drifted widely more than a few times. The terms of the evening were simple: Chatham House rules (which means we don’t talk about what we discussed without permission), so everyone was free to throw out outlandish ideas for discussion, including ones that were maybe not ready for prime time or even mentionable in polite conversation. Basically, everyone agreed not to get offended when their pet ideas were shot down. Often in flames. (Cue sounds of falling planes and explosions!)

While everyone was polite, there were no shy participants at the table. I don’t think I’m far off in describing the conversation as pleasant, spirited, and entertainingly aggressive. I rather admired the senator, as he was willing to fully engage in the give-and-take and did not take offense (or worse, simply write people off), as some politicians do when you suggest that they’re simply wrong. Rand takes up the challenge and presses you on your thoughts. He has a very sharp intellect that has been well honed in conservative thought from the crib.

This was my first time to meet Rand (although protocol says you have to call him Senator). I couldn’t help but contrast the Senator with his father, Ron Paul, whom I have known for 30 years. They are clearly of a different generation, though the apple has not fallen far from the tree. There is a decided libertarian strain in the son. (Which, you might have gathered if you are longtime reader, is a political stance I am quite comfortable with.) But there is a very different quality and texture to Rand’s version of how that philosophy plays out in the context of organizing a country. (That is different from running a country, which he would contend is not something that politicians should do.) I note that yesterday Senator Rand ran well ahead of the second-place finisher in the rather archly conservative CPAC straw poll. In the past that has not meant very much in the broader political scheme of things, but I think Rand’s rather libertarian thinking may appeal to a broader swath of young people than some of us oldsters might think. We will see.

It was a memorable evening. I think I can speak for the group in saying that it was a learning experience for all of us. I am not sure I will get invited to participate again, but I learned a great deal more than I gave. I live for nights like that.

It truly is time to hit the send button. I almost sheepishly confess that I’m going to see the movie Mr. Peabody & Sherman in a bit. For those of us of a certain age, Rocky and Bullwinkle were fixtures in our lives, and Mr. Peabody was my favorite. Gods, I loved the Wayback Machine! I know it’s just nostalgia, but I am so susceptible at times. Have a great week and try to find a conversation of your own from which everybody walks away with more than they brought to the table.

Your looking way back and thinking way ahead analyst,

John Mauldin

P.S. If you like my letters, you'll love reading Over My Shoulder with serious economic analysis from my global network, at a surprisingly affordable price. Click here to learn more.

Put Mauldin Economics to work in your portfolio. Your financial journey is unique, and so are your needs. That's why we suggest the following options to suit your preferences:

-

John’s curated thoughts: John Mauldin and editor Patrick Watson share the best research notes and reports of the week, along with a summary of key takeaways. In a world awash with information, John and Patrick help you find the most important insights of the week, from our network of economists and analysts. Read by over 7,500 members. See the full details here.

-

Invest in longevity: Transformative Age delivers proven ways to extend your healthy lifespan, and helps you invest in the world’s most cutting-edge health and biotech companies. See more here.

-

Macro investing: Our flagship investment research service is led by Mauldin Economics partner Ed D’Agostino. His thematic approach to investing gives you a portfolio that will benefit from the economy’s most exciting trends—before they are well known. Go here to learn more about Macro Advantage.

Read important disclosures here.

YOUR USE OF THESE MATERIALS IS SUBJECT TO THE TERMS OF THESE DISCLOSURES.

Recent Articles

AI and Creative Destruction

March 6, 2026

The Coming Crisis: Fingers of Instability

February 27, 2026

Conflicting Data, Conflicting Results

February 20, 2026

A Paradigm Shift in Employment

February 13, 2026

Federal Regime Change

February 6, 2026

The Real Affordability Problem

January 30, 2026

Thoughts from the Frontline

Follow John Mauldin as he uncovers the truth behind, and beyond, the financial headlines. This in-depth weekly dispatch helps you understand what's happening in the economy and navigate the markets with confidence.

Let the master guide you through this new decade of living dangerously

John Mauldin's Thoughts from the Frontline

Free in your inbox every Saturday

By opting in you are also consenting to receive Mauldin Economics' marketing emails. You can opt-out from these at any time. Privacy Policy